A fresco capturing the spirit of a Renaissance papacy

In the preface to part one of his Lives of the Artists (1550), Giorgio Vasari explains how the painters and sculptors of his age rescued art from the ‘complete ruin’ into which he believed it had fallen after the collapse of the Roman Empire. This ‘rebirth’, he claimed, was due to artists’ departure from the ‘awkward Greek style’ (that is, Byzantine) prevalent in Italy during the Middle Ages. Rebirth meant returning to antiquity and the classical conception of beauty and form, capturing nature as it really appeared. The chief instrument of this new approach was mathematics, which was employed to achieve perspective, proportion and harmony. Melozzo da Forlì’s Sixtus IV appointing Platina Prefect of the Vatican Library (1477) is a sublime application of these principles, in a fresco that also succeeds in encapsulating the political and personal ambitions of its patron.

Melozzo’s work shows Sixtus IV (r. 1471-84) investing the author and humanist Bartolomeo Sacchi (known as Platina) as head of the Vatican Library in 1475. Originally in the library itself, the fresco was transferred to canvas and is now displayed in the Pinacoteca Vaticana, where it sits alongside fragments of another Roman fresco of Melozzo’s, an Ascension of Christ for the church of Santi Apostoli. The Ascension fragments demonstrate his confidence in the medium of fresco, with bold foreshortening, lucid colour and mastery of perspective. Born in Forlì, near Ravenna (c. 1438), Melozzo was strongly influenced by Piero della Francesca, and the clarity of colour and compositional elements in his Ascension can be traced to della Francesca’s style. In Vatican Library, he again applies these techniques, but what makes the work so compelling is its visual summation of Sixtus’ interests and ambitions as pope: glorifying Rome, humanism, and above all, elevating his family.

Sixtus was born Francesco della Rovere in Celle Ligure in Liguria to a well-off but undistinguished family. After joining the Franciscan Order, he studied philosophy and theology at the University of Pavia and on receiving his doctorate went on to teach, lecturing in Padua, Bologna, Ferrara and Perugia. His classes were well received and he became the personal confessor to Cardinal Bessarion, the hugely cultivated Orthodox monk-cum-Catholic cardinal, who travelled to Italy to as part of a delegation in 1438 to broker a reconciliation between the Eastern and Western churches and eventually ended up staying. Bessarion was a renowned scholar and translator of ancient texts and presided over a nascent humanist academy from his Roman palazzo. Francesco’s proximity to Bessarion testifies to the former’s pedigree as a leading intellectual within the Church as well as his academic allegiances, which lay in the burgeoning world of educated men utterly obsessed with classical texts and the union of ancient philosophy with Christian doctrine.

In 1464, Francesco became Minister General of the Franciscans and within a few years was made a cardinal. On Paul II’s death in 1471, the deeply pious Francesco was elected pope, choosing Sixtus as his pontifical name in homage to Sixtus III, a fifth-century pope who embellished Santa Maria Maggiore (Francesco was profoundly Marian) and other sites in Rome, including Santa Sabina on the Aventine. Sixtus IV’s choice was apt, for he too would go on to furnish Rome with enduring structures, including the Ponte Sisto – the first bridge in the city since antiquity – the Sistine Chapel and restorations to the Acqua Vergine. An early papal bull of Sixtus’ declared refurbishing Rome a priority, on the basis that the capital of Christendom should be the ‘cleanest and most beautiful’, and the inscription to which Platina is pointing in Melozzo’s Vatican Library (which Platina wrote) lists Sixtus’ Roman constructions. Beautifying Rome was of dual use to Sixtus, reflecting both the Church’s power and the prestige of his family. The Sistine Chapel, decorated with frescoes by Ghirlandaio, Signorelli, Botticelli and others, is the crowning testament to these twin goals.

The second theme pervading Melozzo’s fresco is antiquity, its classical aesthetic indicative of the humanist milieu to which Sixtus belonged. The Vatican Library was a manuscript repository, and the collection of manuscripts was a task central to humanist activity. To understand this phenomenon, and why theologians and priests were captivated by classical, specifically Neoplatonic, thought, we have to disentangle ourselves from the distinction drawn today between humanism and theology, and the chasm between the secular and religious spheres. In the fourteenth century ‘the vast majority of humanists were patently sincere Christians who wished to apply their enthusiasm to the exploration and proclamation of their faith’.[1] Sixtus’ interest in classical texts was not considered strange nor as necessarily contrary to the beliefs held by the Church of which he was the head.

The seriousness with which educated men treated classical texts is reflected in the grand, formal ceremony depicted by Melozzo. This was the age of manuscript collection and of their translation, and here we have the pope lending official backing to the activity, not only in having a humanist made prefect of the Church’s library, but also by having the event recorded by Melozzo. Not that Sixtus’ humanism was limited to books; in 1471, Sixtus donated antiquities to the Palazzo dei Conservatori on the Capitoline, objects that would form the core of the Capitoline Museums, the world’s first museum. The placing of the antiquities – the She-Wolf bronze (Romulus and Remus were added later by Andrea del Pollaiuolo), colossal head of Constantine and the Spinario, a bronze Hellenistic youth removing a thorn from his foot – on the Capitoline ‘effectively transformed the seat of political power [the Capitoline] into the symbolic cultural center that it remains today’.[2]

Giving the Romans these antiquities was a political move, a lavish dispense reminding the city authorties on the Capitoline who was in charge. But it was also a means of positioning the people of Rome and the city in relation to their classical antecedents, giving the Romans a visual aide–mémoire stressing their link to their illustrious ancestors and drawing a line from the Caesars to the popes. It was a move wholly within the spirit of the age, which was as much preoccupied with looking back as it was exploring the future. Sixtus’ donation of these works to the city was thus directly in step with his humanist, classical interests. Melozzo’s fresco, with its classical pillars, arches and architectural details, as well as its topic, is a mirror of Sixtus’ (and Platina’s) intellectual proclivities. With these developments as a background, we can understand the fresco as Sixtus’ desire to have his intellectual interests recognised and recorded.

However, a closer look at the life of one of the principle figures in Vatican Library reveals the tensions inherent between the Church and humanism that would later be vividly played out. Sixtus’ predecessor Paul II had imprisoned Platina and other humanist members of the Roman Academy on charges of heresy and of planning to assassinate him. Platina’s arrest exposed the latent threat humanism posed to the Church. After all, Lorenzo Valla had, in 1439, revealed the Donation of Constantine – a document that detailed the handing of authority in Rome from Constantine to the popes – as a fake. On Platina’s release, and with Sixtus’ backing, he went on to write a history of the popes (Vitae Pontificum) that excoriated Paul II as an enemy of science and Sixtus’ formal recognition of Platina tells us where Sixtus’ intellectual sympathies lay. Nevertheless, Sixtus was no proto-Enlightenment figure; the year after Melozzo finished Vatican Library, he granted Isabella and Ferdinand the right to establish in Spain the Inquisition of lasting infamy.

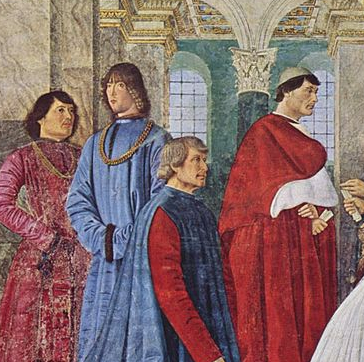

Alongside his abiding interest in humanism, and his desire to give Rome buildings worthy of its spiritual status, Sixtus had another indefatigable goal, which was to promote his family. Thus we come to the third great theme of Melozzo’s fresco; Platina is the only individual included not related to Sixtus – every figure standing is a Sixtus nephew. Not for nothing is Sixtus counted among the Renaissance popes infamous for their nepotism, and this fresco does him no favours in escaping the charge. Beginning on the far left we have Giovanni della Rovere, who in 1475 was made Prefect of Rome, a hereditary, secular title. Thanks to Sixtus’ engineering, Giovanni married Giovanna da Montefeltro, and their son became the Duke of Urbino – a brilliant victory by the man from nowhere, Sixtus, for the della Rovere.

Second left is Girolamo Riario, described unflatteringly by Machiavelli as of a bassissima e vile condizione [a very low and disgusting character].[3] In 1473, Sixtus made Girolamo Lord of Imola in the Romagna, and in attempt at further familial advancement in northern Italy, Girolamo was a protagonist in the Pazzi Consipiracy – a murderous plot to oust the Medici from Florence – which took place the year Melozzo’s fresco was created. Married to the indomitable Caterina Sforza, Girolamo was in 1488 assassinated in Melozzo’s hometown of Forlì. Standing in the centre is Giuliano della Rovere, later and better known as Pope Julius II (r. 1503-13). Giuliano was made a cardinal just four months after Sixtus assumed the papal throne, and was handed Sixtus’ former titular church of San Pietro in Vincoli. Sixtus bestowed an eye-watering eight bishoprics on Giuliano, who would go on to become one of the most famous Renaissance popes, not only a patron of Bramante, Raphael and Michelangelo, but also leading his own troops into battle, demolishing Old St. Peter’s and beginning the new basilica, and, perhaps most controversially of all, growing a beard.

Finally, standing directly next to Sixtus is Pietro Riario (though some claim it is Raffaele Riario depicted), who had died three years before Melozzo set to work. Pietro was the son of Sixtus’ youngest sister Bianca. He was made a cardinal at 26 and given the church of San Sisto, an ancient church named after a previous Sixtus pope. In total, two sets of brothers, two cardinals, one Prefect and one Lord – all within a few short years of Sixtus’ pontificate. Tensions inevitably existed between these men, especially Giuliano and Girolamo, the two central figures, Giuliano allied to the French and the Roman Colonna family, Girolamo with the Spanish and Orisini clan. Their rivalry endured the length of Sixtus’ reign, and, despite not being his uncle’s favourite, Giuliano would emerge victorious, assuming the throne of St. Peter in 1503. Yet it would be a mistake to assume that Sixtus’ dynastic dreams were satisfied with the nephews in Melozzo’s fresco. At then end of 1477, three more Sixtus relations were promoted to the cardinalate. This unblushing nepotism and egregious flouting of papal convention mean that for all of Sixtus’ architectural adornments to Rome, his reputation remains tarnished.

Sixtus’ obsessions – humanism, a desire to embellish Rome and the promotion of his family – are all embodied in Melozzo’s fresco. The setting is an imaginary classical arcade, lined with marble pillars, arches, a gilded coffer ceiling and a half-hidden single Corinthian column in the background. The architectural details are superbly executed, adding to the illusion of looking in on a real place as well as neatly framing the scene. A key passage in Leon Battista Alberti’s De Pictura, written in 1435, is Alberti’s description of composing a painting by imagining an ‘open window’ through which you look upon a scene, a message clearly absorbed by Melozzo. On top of this function, Melozzo’s architectural details, including his careful rendering of the intricate features of the cornice and the exuberant ceiling, reinforces the wealth, power and luxury of the della Rovere. The floral panels, decorated in della Rovere oak, are a gilded aperçu of this message placed in the fresco’s foreground.

The six figures populating the scene are formal and rather stiff, with a posed, self-conscious air, a sensation heightened by Platina’s averted gaze but sly finger directing the viewer to his inscription. But there is no doubt as to their wish to be seen; we are being invited to look in on the ceremony and the people depicted, by the way they stand and by their expressions, know that we are looking in on it – the viewer is therefore a participant in the fresco, not just looking in unobserved on a moment but being encouraged to look and witness what is going on. This relationship between the people depicted and the viewer gives the work a sense of interaction that not even Sixtus’ uncompromising refusal to face the viewer can usurp.

The invitation extended to the viewer is not without limits. The opulence of the setting and of each individual’s dress allows no concession to equality. This distance is amplified by the fact that no figure looks out at the viewer, whose line of sight is slightly beneath the depicted scene. The viewer is not being asked to look in as an equal, then, but as a tolerated observer to see the glory and prestige of Sixtus’ pontificate and of his family. Melozzo has distilled these contrary impulses of distance and proximity with aplomb, and his composition is likewise deftly handled; all of the figures stand in the foreground in a rather narrow space, but Melozzo’s use of perspective in depicting the receding columns and ceiling gives the illusion of a real three-dimensional world, populated by real people.

It is highly accomplished work, with bold colours, superbly executed perspective, trompe-l’œil effects and intricate rendering of architectural details. Though they would not have used the term, this is a Renaissance painting of assuredly Renaissance men who were keen to be seen as such, captured by an artist in complete command of fresco, a difficult medium to master. Vasari would surely have approved.

References

[2] Marciari 2017: 66

[1] MacCulloch 2004: 70

[3] Majanlahti 2006: 76

Bibliography

MacCulloch, D. 2004. Reformation: Europe’s House Divided 1490 – 1700. London.

Majanlahti, A. 2006. The Families Who Made Rome: A History and a Guide. London.

Marciari, J. 2017. Art of Renaissance Rome: Artists and Patrons in the Eternal City. London.